Why sodium-ion can’t yet challenge lithium-ion’s reign

The basic structure of Na-ion batteries closely resembles that of Li-ion batteries, consisting of positive and negative electrodes, an electrolyte, and a separator. Round-trip efficiencies are similar to Li-ion at 90-plus percentages, but sodium’s larger particle size results in Na-ion batteries being bulkier and heavier.

Hithium’s one-hour battery energy storage system (BESS) was the latest product anouncement featuring a 162 Ah Na-ion cell, which the company says has a lifespan of 20,000 cycles. The product was launched last year at the RE+ exhibition in the United States and is positioned to address sudden load spikes in data centers while offering a longer lifespan.

Even if that claim proves true, a critical concern remains: Hithium did not disclose the data needed to assess power density, and Na-ion inherently has lower power density than Li-ion – an important disadvantage for the intended application of ensuring power quality, though not an absolute impediment.

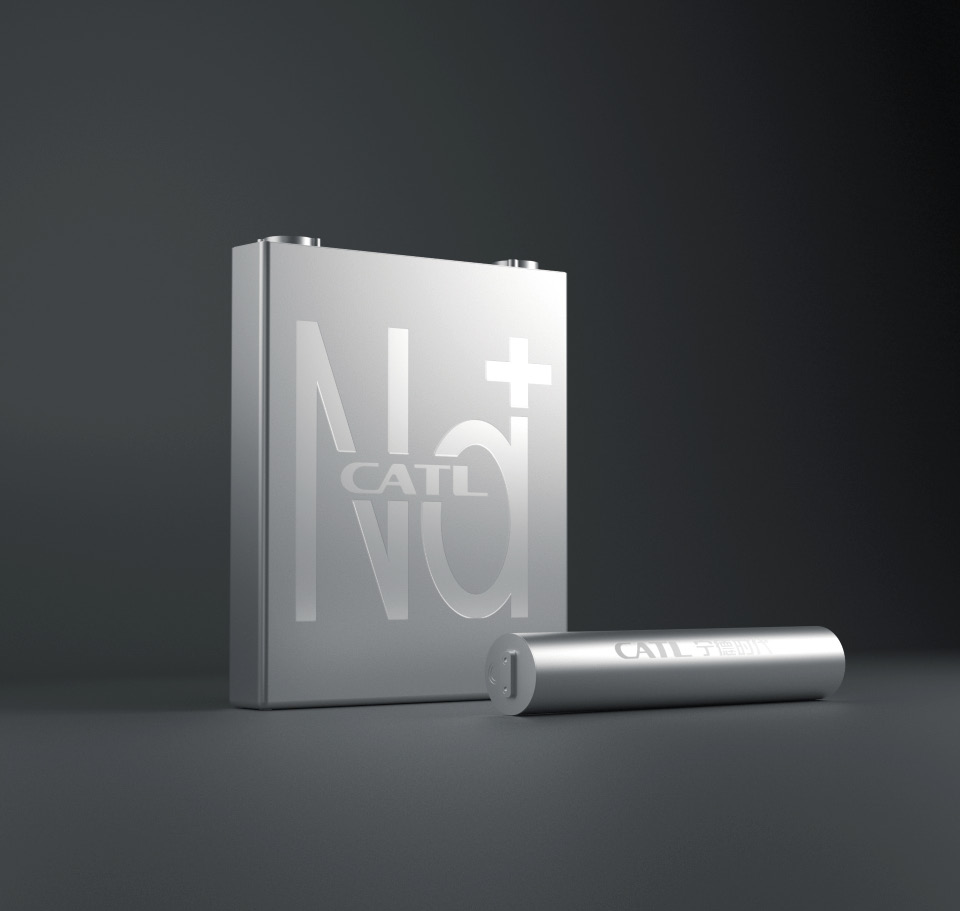

Earlier in 2025, CATL launched its Naxtra Na-ion cell targeting the electric vehicle (EV) market, with a gravimetric energy density of 175 Wh/kg – very close to average lithium iron phosphate (LFP) – and a charge rate at 5 C. HiNa launched a similar product with 165 Wh/kg energy density. However, the most advanced LFP batteries achieve as high as 205 Wh/kg and charge at 12 C. This means that even at their new parameters, Na-ion will need to be relatively cheaper than average LFP and substantially cheaper than cutting-edge LFP to break through the niche status.

Challenges ahead

This is still far from being the case. The lack of scale significantly harms Na-ion’s manufacturing cost, which is estimated to be at least 30% higher than Li-ion at the moment, despite the potential to cost less in the future due to the use of cheaper raw materials. Sodium carbonate used in Na-ion batteries is far less expensive than lithium carbonate. The first is priced in the hundreds of dollars per metric ton, while the latter is in the thousands. Other materials employed, such as aluminum for current collectors instead of copper, are also more affordable. Even so, achieving cost competitiveness will require large investments and scaling of production, which is not supported by existing demand.

In the BESS context, Na-ion’s current cost disadvantage is accompanied by other, inherent, disadvantages – in this case, regarding volumetric energy density. Using two existing products as an example, BYD’s Li-ion-powered MC Cube system has a capacity of 6.4 MWh in a 20-foot equivalent size, while the same system from the same supplier with Na-ion cells only reaches 2.3 MWh. This disparity highlights the immense challenges faced by Na-ion batteries, which are uncompetitive in terms of cost and energy density. This is reflected in demand. Even in China, where most of the Na-ion developments for BESS are taking place, demand for the products is still virtually non-existent. S&P Global Commodity Insights’ Clean Energy Technology service has only recorded 148 MWh of completed Na-ion BESS installations.

But it’s not all bad news for Na-ion. One of its most significant advantages is its safety profile. Na-ion batteries are less prone to thermal runaway, a risk associated with Li-ion batteries that can lead to fires and explosions. Recent innovations have led to the development of Na-ion cells able to withstand extreme conditions without compromising safety. For instance, CATL’s Naxtra cell has demonstrated impressive performance in stress tests, showcasing its ability to endure rigorous conditions without gas venting. Na-ion is also inherently more tolerant to extreme temperatures than Li-ion, which can be an important advantage in certain regions.

In addition to the physical safety component, Na-ion represents a strategic “supply chain safety” element. China dominates the entire supply chain of Li-ion batteries, except for raw materials, where it still relies heavily on imports from countries with lithium wealth, such as Australia, Chile and Argentina. Unlike lithium, sodium can be produced synthetically anywhere, eliminating risks associated with supply chain concentration and price volatility. Dominating the Na-ion technology can be strategic for cell manufacturers that want to hedge their exposure to future shocks in the Li-ion value chain.

Fierce competition

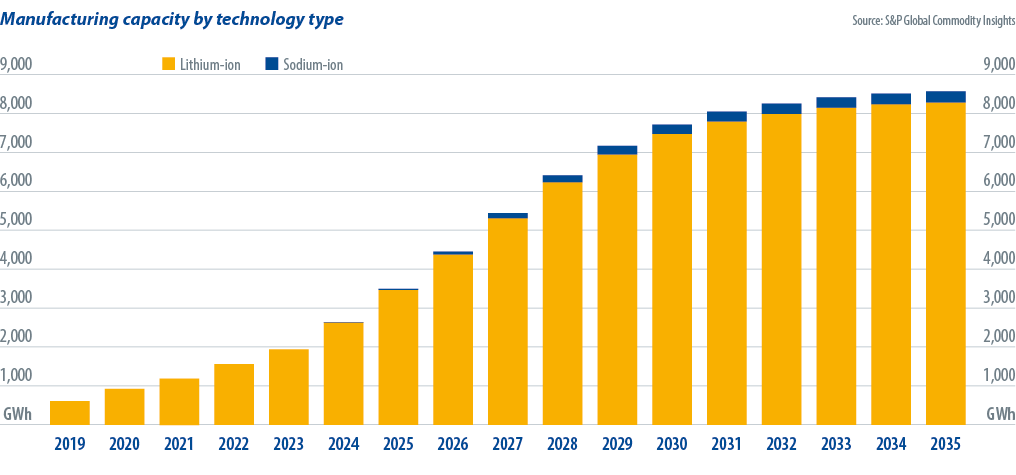

Despite the potential benefits of Na-ion batteries, they face huge competition from Li-ion technology, which continues to evolve rapidly. The same manufacturers that have been progressing on the Na-ion front, such as BYD, CATL and Hithium, have also made substantial advancements in Li-ion technology, overshadowing Na-ion developments with increasingly lower cost and innovative products. The investments in research and development for Li-ion batteries significantly exceed those for Na-ion, making it challenging for Na-ion to reduce the technological disadvantage to Li-ion.

While Na-ion technology may find a niche in specific applications, possibly as starter batteries for passenger and commercial vehicles, or in energy storage use cases where safety and/or temperature tolerance are top priorities, it is essential to temper expectations regarding its impact on the overall battery market. Na-ion batteries are unlikely to disrupt the established dominance of Li-ion technology, which continues to improve in terms of performance and cost at a much faster pace than Na-ion or any other alternative storage technology.

The future of Na-ion technology depends on overcoming several critical challenges. Achieving cost competitiveness and improving energy density are paramount for Na-ion batteries to transition from niche status to a more prominent role in the energy storage landscape. Continued research and development – and more than anything, scaling production to realize economies of scale – will be essential for realizing the full potential of Na-ion technology.

About the author:

Henrique Ribeiro is a principal analyst on the batteries and energy storage team at S&P Global Commodity Insights, focusing on Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula. Ribeiro spent 11 years on the metals pricing team, helping establish benchmarks for global battery metals and for steel and aluminum prices in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. He has spoken at several conferences on battery metals market trends and was a host of the Platts Future Energy Podcast.