‘Italy could have potassium battery gigafactory by 2030’

Silvia Bodoardo believes sodium and potassium batteries could fit into a technology mix dominated by lithium for mobility, but which features a range of different technology for stationary storage use.

The professor, who is a scientific advisor for the Batteries European Partnership Association noted optimal battery performance depends on various factors including operating temperature and potential seismic risk, something which would reduce the use of primarily vanadium-based flow batteries.

“I don’t think there will be standardization in the battery pack because the great advantage of batteries is precisely the possibility of building them tailor-made, for each type of application,” Bodoardo told pv magazine Italia. “You can optimize everything, not just the battery but also the entire system.”

The Polytechnic University of Turin’s potassium-ion battery project, which began in November, has a five-year duration. Its first gigafactories could be built around 2030.

“That’s if we go fast enough,” said Bodoardo. “We have some pretty interesting results.” She stressed, however, industrialization and laboratory results are conceptually different processes.

The university’s electrochemistry group has “skipped” sodium to focus on potassium batteries and is using knowhow accumulated over two decades, especially in lithium.

“The operating mechanism is not that different from that of lithium-ion batteries but the potassium ion is a much larger ion, let’s say, and therefore much more difficult to move,” Bodoardo said, emphasizing the potential role of potassium batteries in the world of stationary storage, rather than e-mobility.

The professor said the study of electrolytes is necessary for the optimization of batteries, in terms of duration – specifically life cycles. That subject is particularly relevant for stationary batteries, said Bodoardo.

Potassium batteries, due to the lower density of the material, would be larger than lithium devices, requiring around 30% more space.

The Italian university is also trying to develop battery materials with a natural origin, for example carbons rather than “critical material” graphite.

“If I start with a new technology and use elements or technologies that are not critical in themselves, I’m on the right track,” said Bodoardo. “The really difficult thing is not to use fluorinated solvents, because of their stability.”

Turin Polytechnic coordinates the European Gigagreen project, for the production of cells, and is the only Italian university with a pilot production line. Bodoardo said production must be as little energy-intensive as possible.

Sodium batteries

“Sodium ion cells are already commercial and a specific roadmap has also been presented for them,” said the professor. “It is a technology that today costs more than 25% more than lithium ion technologies because, at this time, the scale effect has not yet been achieved.” She added, however, “It is extremely likely that sodium batteries will cost less, given the availability of sodium. The same goes for potassium batteries.”

Insurance companies have no historical performance to enable them to evaluate the duration of sodium batteries but, as Bodoardo pointed out, the lifetime of lithium devices has been longer than initially expected, in many cases.

“It must be said that, in general, the average life of the battery is not only tested but it is also modeled,” said Bodoardo. “That is, knowing all the parameters, the duration – the life expectancy – of the battery itself is calculated.”

Insurance companies insure lithium batteries for seven to eight years. “In reality, after 10 years many batteries are still above 80% state of charge, which is considered an acceptable level,” added the professor.

New frontiers

Bodoardo said Turin Polytechnic has extensive expertise in lithium, both on the laboratory cell and production side, for the manufacture of entire battery packs.

“This knowhow has allowed us to tackle even very distant technologies such as lithium oxygen, or lithium sulfur, which have energy densities five to 10 times the theoretical one of lithium ion,” said the professor, while accepting problems with the basic chemistry of such devices remain.

The university, which has three PhD students paid by Stellantis, collaborates with energy and industrial players including Edison and Enel X.

“All technologies that don’t use metals – such as lithium or sulfur, metal-air, and so on – are all ‘Generation Five’,” said the professor. “These are technologies that will perhaps be commercially available in five to 10 years. The entire solid-state sector is currently receiving a lot of attention and research projects based on lithium, which promise high safety and performance.”

Some stages of lithium-ion cell production are performed in dry rooms: large, completely dry chambers. That is because it’s necessary to use non-aqueous solvents. The challenge is to use a production process that avoids organic solvents as much as possible, reducing environmental impact and energy use. That is a significant engineering challenge.

The professor said the scientific community is asking European authorities to push for new chemicals that can be used in the current generation of production technology.

“We risk making a huge effort to build a gigafactory and then shifting our focus to other, incompatible technologies,” said Bodoardo. “That way, we’d never achieve large-scale battery production with good technologies in Europe.

European manufacture, Italian research

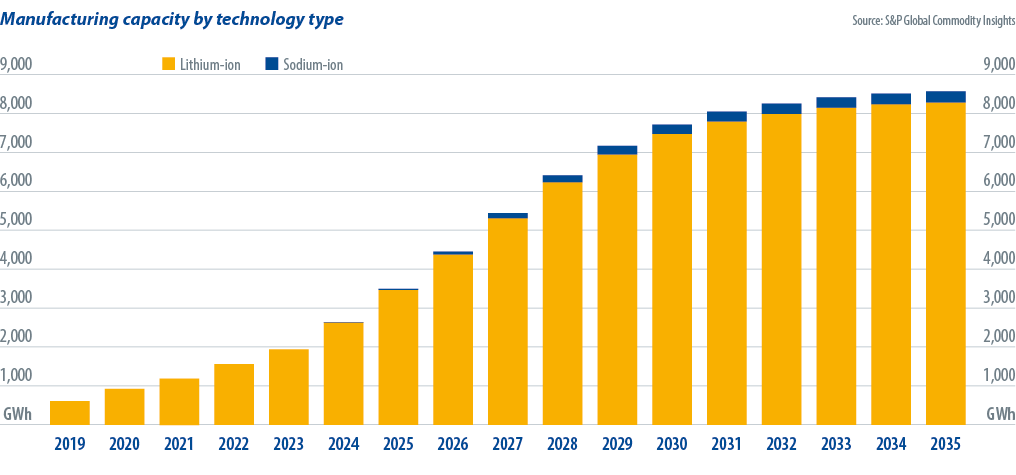

“In Europe, we started by trying to build around 38 gigafactories in a few years. Then things slowed down a bit; however, cell production is continuing to grow in Europe. Not at the rapid rate expected but it’s continuing to grow. Several cell manufacturing companies are already operating in Europe and there’s even a megafactory in Italy: FAAM is a company in the Caserta area that’s building a gigafactory for the production of cells for stationary applications.”

Eni and Seri Industrial have reached agreement for the potential development of the lithium-iron-phosphate electrochemical battery industry. The agreement, as stated in a press release published in October 2024, “explores the possibility of establishing a joint venture to build a stationary electricity storage plant; a production line for active materials (the input for the production process); and a battery recycling plant at Eni’s Brindisi site. This will complement a similar plant currently being built by FIB, a subsidiary of Seri Industrial, in the province of Caserta.”

Bodoardo highlighted the opportunity, which appears to have vanished, for a Stellantis battery production plant in Termoli.

“The Termoli project isn’t actually over yet,” said the professor, recalling the role energy prices played in Stellantis’ decision to potentially opt for starting production in Spain.

From pv magazine Italia.