Making sense of CAISO’s bid cost recovery mechanism and what it means for batteries

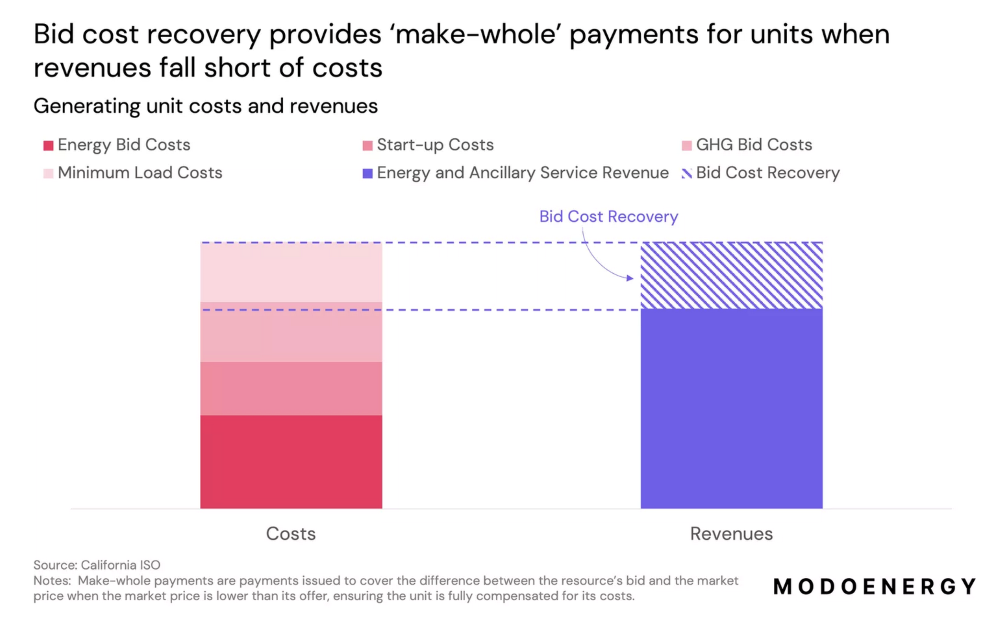

California’s electricity market is built on a complex foundation of incentives designed to keep the grid reliable and resources compensated fairly. Bid cost recovery (BCR) is one such incentive that’s becoming an increasingly important settlement mechanism for energy storage systems in the state.

“It’s important to understand why BCR was originally created,” said Ovais Kashif, a U.S. power market analyst at market research firm Modo Energy. He told ESS News that the program was built to provide a kind of safety net for gas generators; the goal is to ensure that they aren’t left operating at a loss from following CAISO’s instructions.

When the ISO relied primarily on gas and thermal plants, Kashif explained, generators would submit bids in the day-ahead market, commit fuel and begin ramping up hours before dispatch.

But market conditions can change, causing CAISO to decide that the previously committed generation is no longer needed. In those cases, BCR compensates generators for the costs they had already incurred from preparing their systems to run.

It’s essentially a “make-whole” mechanism that tries to ensure generators are fairly treated for being willing to commit in advance and then being told to stand down.

Batteries, however, are a different story.

“They don’t have fuel costs or the same ramping requirements,” Kashif noted, adding that batteries do have opportunity costs, or what they could have earned if they discharged at a different time. “If they agree to discharge at 6 p.m. but the operator says to come online at 5 p.m., you’d fail your prior obligation and incur a penalty. BCR makes the resource whole.”

Herein lies the key difference between how BCR impacts batteries and gas generators: while conventional plants rely on BCR to cover sunk costs like fuel procurement, batteries rely on it to balance missed revenue opportunities when reality differs from projections.

“For short-duration, high-frequency assets like batteries, there are two flavors of how CAISO can take the wheel and drive the asset differently than the operator would like,” Kashif explained. “Either they’re told to stop prematurely or they run out of power too quickly.”

BCR helps the asset balance out, he noted. Under the mechanism, CAISO plots a resource’s eligible costs against its actual revenues in both of its markets (day-ahead and real-time).

“If your real-time price is higher and your costs exceed your revenues, CAISO awards you for being dispatched out of merit and then makes you whole for your original plan,” Kashif explained. If revenues exceed costs, no payment is made.

Still, while it may sound like a great bang-for-your-buck mechanism for battery revenues, BCR isn’t the headline item for most investors.

“Maybe 5% of a battery’s annual revenue will be labeled as BCR, which ends up mostly making whole for other things,” Kashif said, adding that it’s “not a significant part” of the business case compared to energy arbitrage, resource adequacy or ancillary services

But from CAISO’s perspective, the way batteries perform under BCR has changed the game. Compared to gas, batteries receive more BCR payments per unit of energy delivered; the average battery receives about nine times more payments than a typical generator.

While the program wasn’t originally designed for battery storage, Kashif said, CAISO relies on it to compensate batteries for providing flexibility.